Jürgen Habermas Still Believes in Modernity

In 2019, Jürgen Habermas—perhaps Europe’s most well-known living philosopher—published his long-awaited Auch eine Geschichte der Philosophie (“This Too a History of Philosophy”), a nearly 2,000-page history of Western philosophy. Habermas is famous for his work on the democratic public sphere, and Auch eine Geschichte der Philosophie sought to explain its philosophical origins by showing how faith and knowledge have related to one another from antiquity through the Middle Ages until the modern age. In this manner, Habermas offered a story about how the tensions between religion—the book primarily focuses on the moral universalism of Christianity, that emerged from Judaism—and philosophy entailed a kind of 3,000-year “learning process.” The result, Habermas suggests, has been a migration of theological content into “the realm of the secular, the profane.” In this way, Habermas connects the establishment of monotheism to the rise of the natural sciences, individual freedom, and liberal democracy. At the same time, even as he believes that Western liberal democracies have profound religious origins, he shows how modern philosophy gradually detached itself from its symbiosis with religion and became secularized.

To what degree, though, does modern Western reason remain indebted to religious sources? Can it now stand on its own absent the dialogue between faith and reason that, according to Habermas, gave rise to the democratic public sphere? These questions are worth asking given that Western liberal democracies now find themselves in a profound state of crisis. On the occasion of the recent English translation of his history of Western philosophy, The Nation spoke with Habermas about these questions.

Daniel Steinmetz-Jenkins: The title of your book, Also a History of Philosophy, immediately arouses curiosity, and specifically about what the “also” might mean. Why did you choose this title?

Jürgen Habermas: At first glance, this is simply a gesture of modesty. Every history reveals the author’s perspective. I even need the entire first volume of a three-volume English translation to explain my perspective. On closer inspection, however, my approach to the history of Western philosophy is distinctive—and I want to draw attention to this. I want to demonstrate that “our” modern understanding of reason and autonomy is the result of learning processes. With this endeavor, I am implicitly opposing a frivolous philosophical dismantling of everything that, since Hegel’s reflection on the Age of Enlightenment, has been called the critical self-understanding of modernity. Because this is endangered today.

JH: We are witnessing a profusion of studies, among my colleagues in the social sciences and in other disciplines, that simply assume the end of modernity with a certain matter-of-factness, even callousness. And indeed, there are many empirical signs that not only are the great political achievements of modernity under threat, but also that the intellectual mood in general is turning against the very motifs of the Enlightenment from which the political West has hitherto drawn its strength.

What I find most striking about these shoulder-shrugging dismissals of an epoch is the insensitivity to the fact that this modern way of thinking has been conducted in a self-critical manner from the very beginning. Such an intellectual heritage, whose very mode of transmission involves self-transformation, cannot be indifferently brushed aside, and be dismissed and forgotten as a bygone period in human history. But it is equally inadequate today to merely insist once more on a tradition that at one time asserted itself against everything that was sheer tradition. That is why I undertake the task of demonstrating, through a history of philosophy, that our authoritative concepts of reason and autonomy are products of lengthy learning processes. If this can be shown, then these concepts have a completely different resilience. What we have acquired through learning can at best be superseded through further learning. As long as this is not the case, what has been learned can at most be repressed, but not forgotten entirely. As something repressed, it does not disappear but remains effective as resistance.

Philosophy’s public task is to reflexively clarify and improve the kind of everyday understanding of the world and ourselves with which we are always already operating in our daily life. This is what is meant by the expectation that philosophy contributes to “a better understanding of the world.” Philosophy accomplishes this in the light of the best knowledge about the world available in society. In its interpretation, it sees itself particularly challenged by new advances in knowledge or by surprising historical shifts that devalue or expand the current self-understanding.

Today, examples include the role of biogenetic discoveries in reproductive medicine, the role of artificial intelligence processes in the workplace, or the more momentous geopolitical upheavals in the wake of the decline of superpower. Philosophy’s role is to help explain what the revolutionary findings or historical changes mean in each case for us as human beings, contemporaries, and individuals. In any case, philosophy is distinguished from science in the narrower sense by this reflexive reference to the individual and collective understanding of self and the world encountered in society.

Philosophy is certainly a scientific way of thinking, and its mode of developing a scientifically enlightened self-understanding also calls for a scientific approach to processing scientific knowledge of relevance for the lifeworld or to dealing with invasive political changes. However, it is easy to confuse this special role of philosophy with science in general, because scientific activity developed largely within the institutional framework of philosophy until modern natural science emerged and became independent. But in my view, philosophy is distinguished as such by its mode of developing a general self-understanding regarding everything that bears on the background of our orienting knowledge of the world. In this respect, philosophy is certainly not just one among other sciences. It articulates our self-understanding by responding to new knowledge and new life situations, insofar as they disrupt and expand our previous understanding of the world and ourselves.

It is no coincidence, for instance, that my book concludes with chapters on the enabling conditions of cooperative research and on the practices of rational morality and constitutional democracy. Since they are the result of lengthy philosophical learning processes, such achievements can, at worst, be suppressed, but not without leaving traces in history to which later generations can return. Throughout its history, and especially since the advent of modern science, philosophy has repeatedly responded in a similar manner to the increase in knowledge of events in the world and, more broadly, to shocks to our self-understanding.

DSJ: But surely philosophy does not only have an interpretive role, but also generates its own knowledge?

JH: Yes, in this sense philosophy’s own field of research naturally includes the conditions of possibility for perception and knowledge in general as well as those for action and speech. However, its actual theme is more general—as I said, a methodically guided elucidation of that general understanding of the world and of ourselves, on which we and our contemporaries are always already relying for orientation in our life. But a history of philosophy must also address the changes that its role undergoes within its own society. Its most conspicuous role is to make critical contributions to the legitimization of the respective form of political rule.

DSJ: In any case, the book sees the power of modern reason in connection with the development of early religions and ancient worldviews.

JH: It may seem surprising that I make the discourse on faith and knowledge the subject of a history of Western philosophy at all. There are several reasons for this. First, Karl Jaspers convinced me when he argued that Western philosophy belongs to the worldviews that emerged during the so-called axial age, i.e., around the middle of the first millennium BCE, in five or six most advanced civilizations of the time. That is why, before presenting the history of philosophy in the narrow sense, I first offered a brief comparison of the origins of Judaism, Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism, together with classical Greek philosophy up to Plato. This puts the history of Western philosophy at least into perspective. For despite ambitious intercultural discourses sparked by special occasions, we still lack a sufficiently systematic comparison of the historical paths of the major traditions mentioned, which still extend into contemporary political discourses. Conflicting interests are one thing; however, the justifications for them are the only currency in which the pressing problems that must be negotiated in an economically integrated global society can be solved cooperatively.

In our context the examination of the axial age moreover reminds us that modern Western philosophy also emerged from the combination of two worldviews with quite opposed structures. The combination of Platonism and the teachings of early Christianity, which came about during the Roman Empire, influenced Western philosophy for one and a half millennia. I am particularly interested in the momentous consequences that the biblical legacy had as a result. On the one hand, it shaped the ontological presuppositions of modern natural science through nominalism; on the other hand, it determined the history of European natural law through the reception of Roman law.

Today, I think it is especially important to recall how the development toward modern rational natural law, accelerated by the Wars of Religion, already led to Kant’s idea of a “general condition of right” binding on all states. According to this idea, a globally valid system of universal and strictly binding laws should ensure that citizens of all countries are entitled to the same individual rights in principle. The present concept of human rights reflects the principles of Kant’s moral theory: the universality, the individualistic character, and the binding validity of justified norms. However, the historical, political, and social context in which this abstract idea can be realized was first taken seriously by Hegel and the great thinkers who followed him, albeit in a profoundly critical vain. Feuerbach, Marx, Kierkegaard, and the American pragmatists were the first to engage simultaneously with both Kant and Hegel and their religious heritage, thus setting the stage for contemporary philosophy.

DSJ: Your critique of “scientific rationality,” formulated in the late 1960s, exposes scientism as an ideology that legitimizes capitalist societies by reducing rationality to problem solving, politics to administration, and social change to efficiency. In your current book, scientism functions as a response to the loss of metaphysical security, comparable to the literalism of fundamental Christians. How would you describe your attitude toward knowledge and science? Has this attitude changed?

JH: I have never criticized scientific rationality as such. Philosophy also makes use of this rationality. Then as now, my reservations were never directed against scientific enlightenment, much less against the sciences themselves, but rather against the claim to construct a “worldview” based on the results of the various sciences. This tendency was most evident in the logical positivism of the Vienna Circle, which became influential again after the Second World War through the well-known émigrés in the United States. Quite independently of their own important philosophical work, it is that intention which I always found misleading.

The idea of a “scientific worldview” disregards the necessity of connecting up with an understanding of self and the world that philosophy always already encounters among people in the everyday lifeworld. For even in the allusion to the holistic nature of a “picture” of the world as a whole, contained in the notion of a “worldview,” something of the character of that background understanding already present and found in “our” lifeworld is mirrored—and that background understanding is never fully objectifiable. Scientism does not seek to explicate and, if necessary, correct common sense as such with philosophical interpretations, but to replace it with a scientifically constructed worldview.

In the 1960s, I criticized above all the political consequences of that idea, namely the disenfranchisement of democratic citizens by politicians who wanted to use such indoctrination to promote a supposedly unavoidable technocratic regime. That should again sound pretty familiar in the United States of Elon Musk.

DSJ: How influenced are you in the intention of your history of philosophy by Theodor W. Adorno, who assumed that theological content would change and migrate into the realm of the secular?

JH: Adorno was convinced that theological contents will not survive unless they get translated in secular terms. This idea has always moved me. In my book I have traced step by step how the above-mentioned development of Christian natural law into modern rational natural law leads to a discursive justification of basic rights and human rights. In this way, philosophy can provide a reasonable justification of the constitutional principles of the democratic rule of law against the presently growing potential of right-wing extremism. Thus philosophy can provide the constitutional state with a completely different kind of support than the legal positivist view, which ultimately bases the claim to validity of a constitution not on the power of good reasons, but solely on the expression of the will of the legislator.

DSJ: Max Weber is well known for his distinction between facts and values, or between science and politics. According to Weber, science can produce universal knowledge, but cannot create meaning. Meaning can only arise from the interpretation of facts through values. If we follow Weber here, we simultaneously leave the realm of universal truth and are confronted with “rationally incompatible worldviews.” Unlike Weber, you do not share the pessimistic understanding of history that results from Weber’s argument.

JH: Max Weber’s perspective is that of a sociologist and historian who sees history as a battlefield of rival belief systems. Today, history itself lends credence to this perspective, as shown by obvious examples such as the renewed conflict between the nuclear powers India and Pakistan. On the other hand, Weber did not yet have to deal with the counterexample of the establishment of an international order based on human rights. The fact that the United Nations emerged from the horrors of the Second World War may explain why this legal system is recognized by 193 nations. In our context, however, what is interesting is the general fact that norms can claim precedence over the particular values of their various addressees as long as the validity of these norms rests on their being generally recognized. Such consent can be based on compromises and thus on the contingent agreement of different interests. However, this is a shaky basis, since interests can change at any time. For this reason, the validity of legal norms must rest in principle on good reasons that are convincing to all of their addressees. Max Weber fails to recognize the rationality that recognized norms may claim over mere value orientations. Therefore, whether it will be possible to tame the bellicosity of the major powers remains an open political question for the time being. The idea that world history is and remains a slaughterhouse must not be taken as a fact grounded in human nature.

DSJ: The origins of critical theory lie in Marxism, psychoanalysis, and the critique of power, ideology, and domination. These ideas are less present in your book, even though they played a major role in your previous works. Where do you situate your book in relation to critical theory in the broad sense?

JH: In the preface to my book, I referred to the 1937 essay by Horkheimer and Marcuse, “Philosophy and Critical Theory,” from the Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung, which can be considered the founding document of Critical Theory. I remain indebted to this source for the basic social-theoretical assumptions that informed the background of my history of philosophy. But these assumptions themselves are not the theme of the book. On the other hand, if you ask what has become of my connection to the tradition of Western Marxism, I would remind you that the research of Critical Theory was focused from its beginnings on explaining the unexpected stability of capitalism despite all its crises. And as far as my involvement in West German day-to-day politics was concerned, I must confess that, as a leftist, I was mainly preoccupied with the struggle to liberalize the political mentality of a population that initially remained deeply attached to the Nazi regime.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

As far as capitalist development was concerned, a revolutionary transformation of the liberal economic order established since the end of the Second World War was in any case no longer feasible under the conditions of systemic competition with the Soviet regime. And since the end of the Cold War even less so. From the postwar period onwards, my own interest was directed toward welfare state reforms that, if sufficiently radical, could change capitalist democracies beyond recognition. However, in the shadow of the declining superpower, we are currently witnessing the emergence of new fronts with the infiltration of liberal democracies from the right, both nationally and globally Currently, we would be satisfied if our capitalist democracies could defend themselves against a takeover by right-wing populism—but even that might well be no longer possible without extensive reforms of capitalism.

DSJ: You witnessed Germany’s partition after World War II, its unification and the Cold War’s end, and its rise to the leading liberal political economic power on the European continent. Could you have ever imagined the current upheaval being a possibility in the 1990s at a time in which many embraced a philosophy of history that suggested the arrival of history’s end?

JH: Well, I never believed in that naïve idea. However, the current abrupt break with the history of Germany’s continuous rise under the protection of the United States came as a surprise. For me, however, this does not have the meaning of a break with a “philosophy of history” in the usual understanding of the term that sees history progressing toward a goal. After all, this is a different matter from my own endeavor to seek the tailwind of encouraging learning processes on which we can draw, in full awareness of historical contingencies—learning processes with which it would be wise to seek to connect today. Trump’s decision to turn his back on the political tradition of the West has obviously left Germany and Europe as a whole in a rather difficult situation.

DSJ: The Alternative für Deutschland looks to have achieved the status of a mainstream political party, as recently evidenced by Christian Democrats growing willingness to cooperate with it, and especially on anti-immigration policies. Are you stunned by the AfD?

JH: Yes, the continued growth of a party whose leaders are so closely associated with fascist ideas—so closely that even Marine Le Pen’s party in France wants nothing to do with them—is alarming, especially because we have yet to find a plausible explanation for its constant growth. If a key reason is that many voters are overwhelmed by the complexity of the problems that national governments are increasingly grappling with and that these voters are seeking simple solutions in familiar national settings, then I see no easy way out. After the defection of the United States and the political disintegration of the West, the EU has no choice except to change course from its half-hearted status quo policy and develop the ability to act collectively in global politics. Above all, the urgent need to develop a common European defense policy points toward stronger European integration. In a world of geopolitical turmoil, how else can the European states—even Germany as a single state—be taken seriously in international politics? On the other hand, the new chancellor, Friedrich Merz, is still living in the world of Wolfgang Schäuble and views the European question through the blinkers of German economic policy. Given the global political upheavals, I don’t think that the new German government has the necessary stature to meet the extraordinary challenges. It seems unlikely that Europe will be able to escape the maelstrom of the declining superpower and the associated risks.

More from The Nation

Nathan Kernan’s biography of the New York School poet tracks the development of his serene and joyful work alongside the chaos of his life.

Books & the Arts

/

Evan Kindley

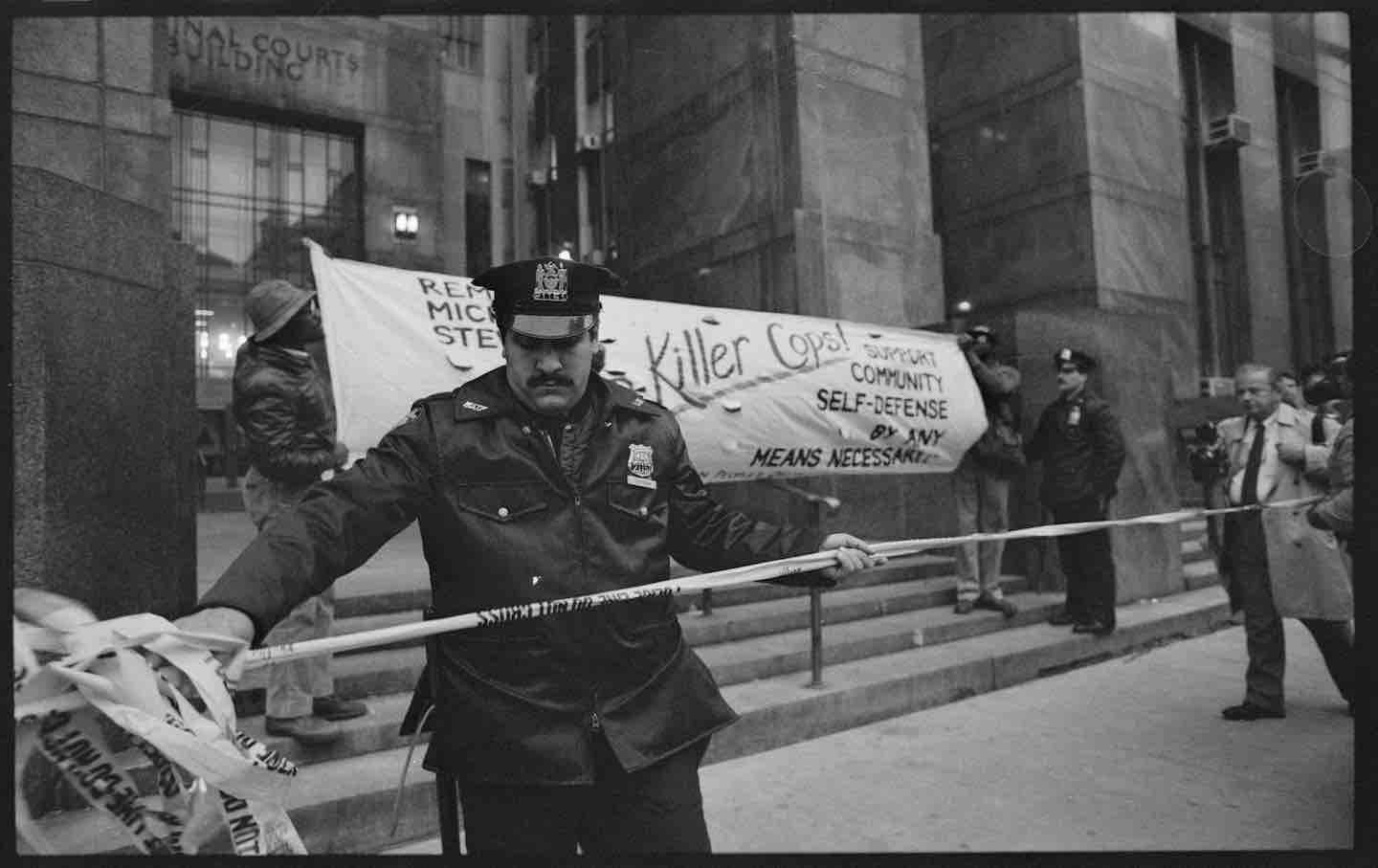

In 1985, police were acquitted in the killing of a graffiti artist and painter, a grisly act that galvanized the city’s art underground. Why has he been forgotten?

Books & the Arts

/

Michael Shorris

Notes to John, posthumously published journal entries chronicling Didion’s therapy sessions, is a peek into the myths and fears that animated her writing life.

Books & the Arts

/

Emma Hager

The Studio is pitched as a send-up of the idiocy of the entertainment industry, but its potshots are harmless, even friendly.

Books & the Arts

/

Vikram Murthi

Post Comment